Tuesday, December 5, 2017 From rOpenSci (https://ropensci.org/blog/2017/12/05/rperseus/). Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under the CC-BY license.

🔗 Introduction

When I was in grad school at Emory, I had a favorite desk in the library. The desk wasn’t particularly cozy or private, but what it lacked in comfort it made up for in real estate. My books and I needed room to operate. Students of the ancient world require many tools, and when jumping between commentaries, lexicons, and interlinears, additional clutter is additional “friction”, i.e., lapses in thought due to frustration. Technical solutions to this clutter exist, but the best ones are proprietary and expensive. Furthermore, they are somewhat inflexible, and you may have to shoehorn your thoughts into their framework. More friction.

Interfacing with the Perseus Digital Library was a popular online alternative. The library includes a catalog of classical texts, a Greek and Latin lexicon, and a word study tool for appearances and references in other literature. If the university library’s reference copies of BDAG1 and Synopsis Quattuor Evangeliorum2 were unavailable, Perseus was our next best thing.

Fast forward several years, and I’ve abandoned my quest to become a biblical scholar. Much to my father’s dismay, I’ve learned writing code is more fun than writing exegesis papers. Still, I enjoy dabbling with dead languages, and it was the desire to wed my two loves, biblical studies and R, that birthed my latest package, rperseus. The goal of this package is to furnish classicists with texts of the ancient world and a toolkit to unpack them.

🔗 Exploratory Data Analysis in Biblical Studies

Working with the Perseus Digital Library was already a trip down memory lane, but here’s an example of how I would have leveraged rperseus many years ago.

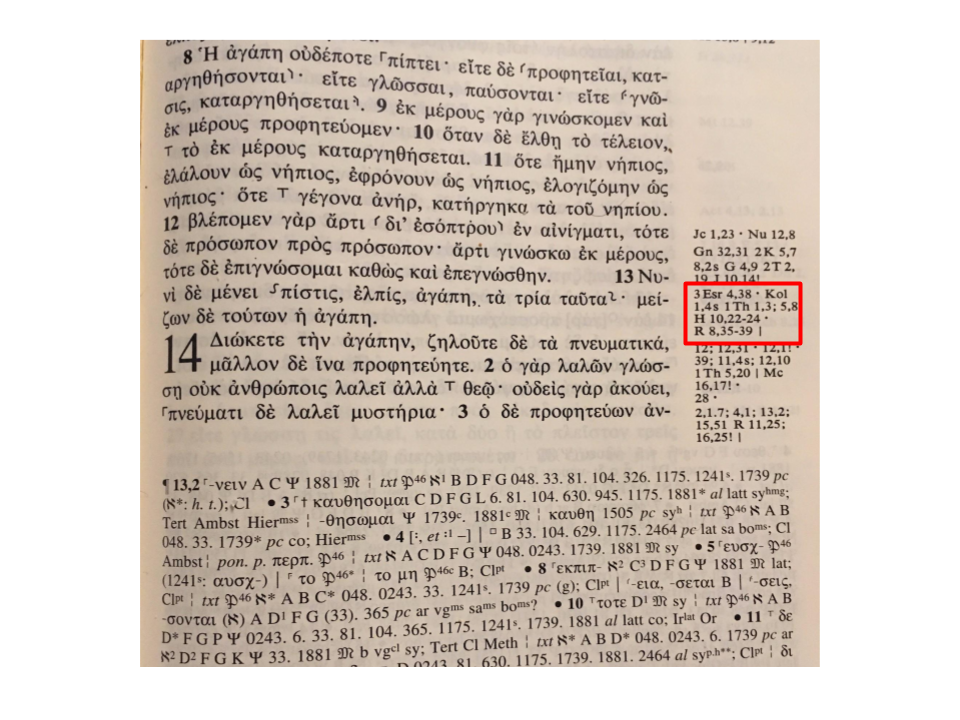

My best papers often sprung from the outer margins of my Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece. Here the editors inserted cross references to parallel vocabulary, themes, and even grammatical constructions. Given the intertextuality of biblical literature, the margins are a rich source of questions: Where else does the author use similar vocabulary? How is the source material used differently? Does the literary context affect our interpretation of a particular word? This is exploratory data analysis in biblical studies.

Unfortunately the excitement of your questions is incommensurate with the tedium of the process–EDA continues by flipping back and forth between books, dog-earring pages, and avoiding paper cuts. rperseus aims to streamline this process with two functions: get_perseus_text and perseus_parallel. The former returns a data frame containing the text from any work in the Perseus Digital Library, and the latter renders a parallel in ggplot2.

Suppose I am writing a paper on different expressions of love in Paul’s letters. Naturally, I start in 1 Corinthians 13, the famed “Love Chapter” often heard at weddings and seen on bumper stickers. I finish the chapter and turn to the margins. In the image below, I see references to Colossians 1:4, 1 Thessalonians 1:3, 5:8, Hebrews 10:22-24, and Romans 8:35-39.

1 Corinithians 13 in Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece

1 Corinithians 13 in Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece

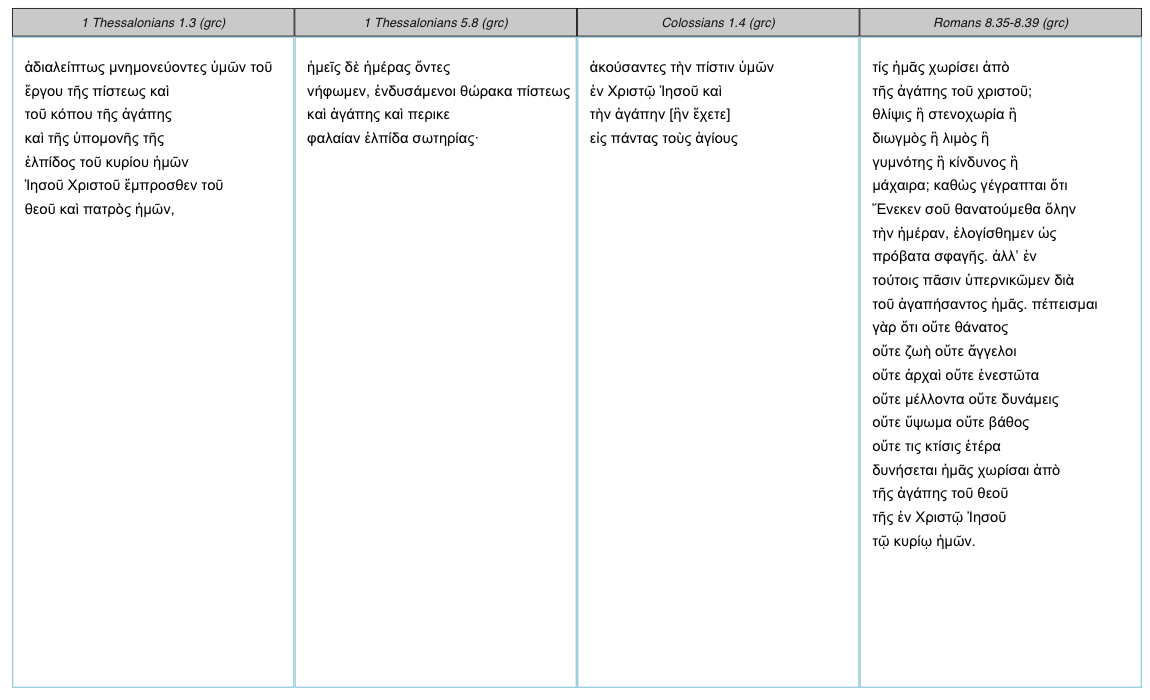

Ignoring that some scholars exclude Colossians from the “authentic” letters, let’s see the references alongside each other:

library(rperseus) #devtools::install_github(“ropensci/rperseus”)

library(tidyverse)

tribble(

~label, ~excerpt,

"Colossians", "1.4",

"1 Thessalonians", "1.3",

"1 Thessalonians", "5.8",

"Romans", "8.35-8.39"

) %>%

left_join(perseus_catalog) %>%

filter(language == "grc") %>%

select(urn, excerpt) %>%

pmap_df(get_perseus_text) %>%

perseus_parallel(words_per_row = 4)

A brief explanation: First, I specify the labels and excerpts within a tibble. Second, I join the lazily loaded perseus_catalog onto the data frame. Third, I filter for the Greek3 and select the columns containing the arguments required for get_perseus_text. Fourth, I map over each urn and excerpt, returning another data frame. Finally, I pipe the output into perseus_parallel.

The key word shared by each passage is agape (“love”). Without going into detail, it might be fruitful to consider the references alongside each other, pondering how the semantic range of agape expands or contracts within the Pauline corpus. Paul had a penchant for appropriating and recasting old ideas–often in slippery and unexpected ways–and your Greek lexicon provides a mere approximation. In other words, how can we move from the dictionary definition of agape towards Paul’s unique vision?

If your Greek is rusty, you can parse each word with parse_excerpt by locating the text’s urn within the perseus_catalog object.

parse_excerpt(urn = "urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0031.tlg012.perseus-grc2", excerpt = "1.4")

| word | form | verse | part_of_speech | person | number | tense | mood | voice | gender | case | degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ἀκούω | ἀκούσαντες | 1.4 | verb | NA | plural | aorist | participle | active | masculine | nominative | NA |

| ὁ | τὴν | 1.4 | article | NA | singular | NA | NA | NA | feminine | accusative | NA |

| πίστις | πίστιν | 1.4 | noun | NA | singular | NA | NA | NA | feminine | accusative | NA |

| ὑμός | ὑμῶν | 1.4 | pronoun | NA | plural | NA | NA | NA | masculine | genative | NA |

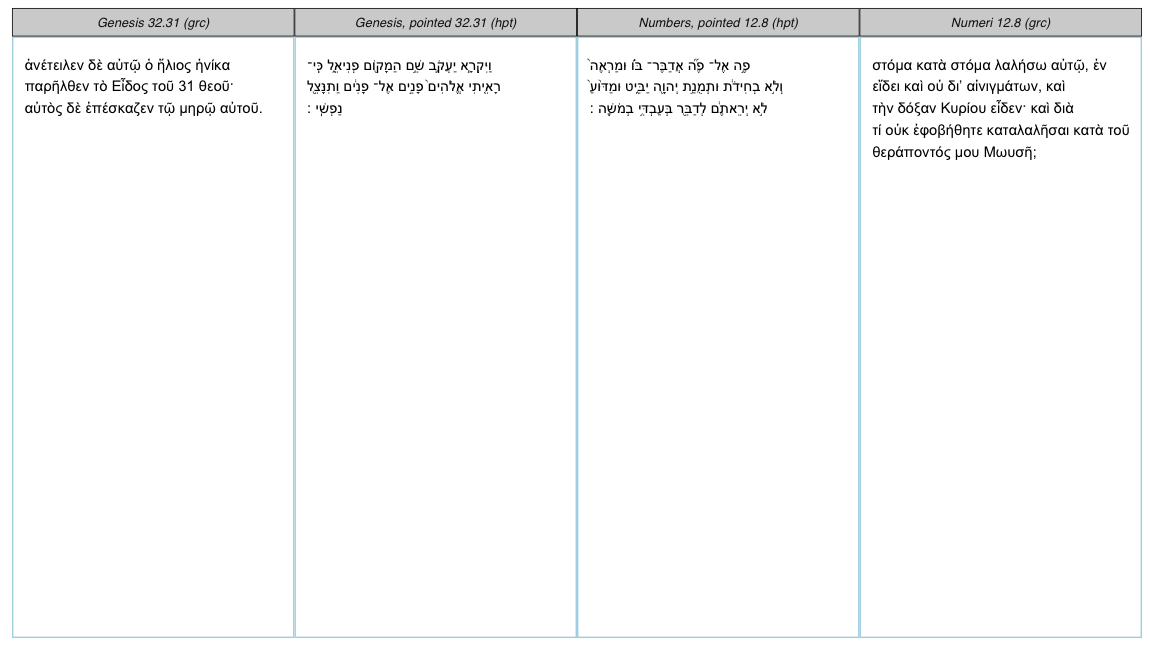

If your Greek is really rusty, you can also flip the language filter to “eng” to view an older English translation.4 And if the margin references a text from the Old Testament, you can call the Septuagint as well as the original Hebrew.5

tribble(

~label, ~excerpt,

"Genesis", "32.31",

"Genesis, pointed", "32.31",

"Numeri", "12.8",

"Numbers, pointed", "12.8"

) %>%

left_join(perseus_catalog) %>%

filter(language %in% c("grc", "hpt")) %>%

select(urn, excerpt) %>%

pmap_df(get_perseus_text) %>%

perseus_parallel()

Admittedly, there is some “friction” here in joining the perseus_catalog onto the initial tibble. There is a learning curve with getting acquainted with the idiosyncrasies of the catalog object. A later release will aim to streamline this workflow.

🔗 Future Work

Check the vignette for a more general overview of rperseus. In the meantime, I look forward to getting more intimately acquainted with the Perseus Digital Library. Tentative plans to extend rperseus a Shiny interface to further reduce “friction” and a method of creating a “book” of custom parallels with bookdown.

🔗 Acknowledgements

I want to thank my two rOpenSci reviewers, Ildikó Czeller and François Michonneau, for coaching me through the review process. They were the first two individuals to ever scrutinize my code, and I was lucky to hear their feedback. rOpenSci onboarding is truly a wonderful process.

Bauer, Walter. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. Edited by Frederick W. Danker. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000. ↩︎

Aland, Kurt. Synopsis Quattuor Evangeliorum. Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1997. ↩︎

The Greek text from the Perseus Digital Library is from 1885 standards. The advancement of textual criticism in the 20th century led to a more stable text you would find in current editions of the Greek New Testament. ↩︎

The English translation is from Rainbow Missions, Inc. World English Bible. Rainbow Missions, Inc.; revision of the American Standard Version of 1901. I’ve toyed with the idea of incorporating more modern translations, but that would require require resources beyond the Perseus Digital Library. ↩︎

“hpt” is the pointed Hebrew text from Codex Leningradensis. ↩︎